CNS Scholarship Winner Gets First-Hand Insight into Computer Science Pioneer Alan Turing

Valeria Gonzalez is the first recipient of the Alan Turing Memorial Scholarship launched by UC San Diego’s Center for Networked Systems (CNS), so she was excited when she learned that the nephew of the famous mathematician and pioneer in the fields of computer science and artificial intelligence would be coming to La Jolla for a speech. The scholarship was established in 2015 by CNS to encourage participation in systems and networking research by students who are active in supporting the LGBT community.

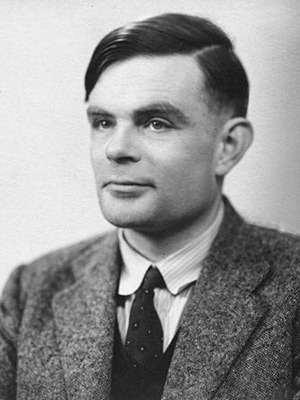

Despite his eminent contributions in cryptanalysis, computer science and artificial intelligence, Turing was imprisoned after World War II for his sexuality, and committed suicide in 1954. His life was the subject of an Academy Award-nominated 2014 film, The Imitation Game.

Sir Dermot Turing is more than just a nephew. He is an Oxford-trained geneticist-turned-solicitor (lawyer) and prolific author, and he was invited to give a public talk by the San Diego Biomedical Research Institute. So it was that Gonzalez, CNS administrator Jennifer Folkestad and former CNS staffer Kathy Krane — who had the original idea of creating a CNS scholarship in honor of Alan Turing — found themselves at The Scripps Research Institute near UC San Diego on October 28 to hear Sir Dermot talk about “Alan Turing: Myth and Methods”, as part of the institute’s Collaboration & Communications Seminar Series.

As detailed in his most recent book, “Professor Alan Turing Decoded”, the younger Turing largely debunks the myths of Alan Turing being a recluse, difficult to deal with, and a poor communicator. Using illustrations from Alan Turing’s work and personal accounts from colleagues of what he was like to work with, Sir Dermot traced the course of Turing’s achievements and described how his uncle arrived at his ideas.

Sir Dermot Turing remains a Trustee of Bletchley Park, the site of Britain’s ambitious effort to crack Germany’s Enigma code in World War II — for which Alan Turing was credited by Winston Churchill as saving millions of lives and making the single most important contribution to the Allied victory over Germany. In addition to being one of the world’s leading cryptanalysts and a founder of the science of artificial intelligence, Turing is widely considered one of the fathers of computer science, and to this day, the Turing Prize remains the top prize in the field — the equivalent of a Nobel for a field not yet a science when the Nobel Prizes were created in 1901.

According to Sir Dermot, his uncle was broadly influenced by mathematician Max Newman. It was a lecture by Newman in 1927, in which Newman mused whether mathematical solutions could be done by a mechanical device, that sparked Turing’s work on computing machines. “Alan Turing takes this thought and produces the amazing paper in which he comes up with the concept of a universal programmable computing machine,” said Sir Dermot. “He envisioned a multipurpose machine whose purpose would change as you feed it different code — something that would have been almost unimaginable in the 1930s.”

One myth debunked by Sir Dermot was that his uncle did all of his work alone. Perhaps his greatest achievement — breaking the German Enigma code in World War II — could not have happened without the work of three Polish mathematicians who reconstructed the German machine physically from intelligence reports in order to test Turing’s code. Further, “Turing wasn’t an engineer,” said Sir Dermot, “but he had a talented collaborator and engineer, Harold (Doc) Keen, to help design the codebreaking machine built at Bletchley following initial experiments with the Polish machine.”

The wartime code-breaking work at Britain’s Bletchley Park led to an effort after the war to tap technology to benefit British industry. “Alan Turing started thinking about turning the concept of a universal computing machine into reality,” Sir Dermot told the audience, eliciting laughter when he noted that “Turing worked on the country’s first major computing project, which evolved out of a debate about whether Britain would need in the long run one or two computing machines.” This was the very dawn of computers, and hence Turing’s reputation as one of the fathers of computer science.In 1950, while teaching at the University of Manchester, Turing also developed a test of a machine’s ability to exhibit intelligent behavior equal or indistinguishable from a human’s intelligence. To this day, the so-called Turing test remains the barometer of fully-developed artificial intelligence.

Turing also made significant contributions in other fields, including developmental biology (which he pursued in the last years of his life), philosophy (heavily influenced by discussions at Cambridge with Austrian-British philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein), and pure mathematics. “People are rediscovering his 1952 paper on the chemical basis of morphogenesis, about how non-uniformity in biological systems may arise naturally out of a homogeneous, uniform state,” said Sir Dermot. “Some experiments in just the last two years reached findings that can only be explained by Alan Turing’s work.”

At his death in 1954, Turing left two unfinished manuscripts that touched on both developmental biology and philosophy.